Will AI cure cancer?

A vision scientist's vision for the future of cancer immunotherapy

For nearly half of my life, I've worked to understand how our eyeballs and brains conspire to make sense of the incredible complexity of the visual world. I have spent a lot of time thinking about the statistics of the world around us, and how we might build better computer vision systems. I pondered the big questions, like "how specialized are cortical circuits for the world around us?", and "are faces special or just another category of object?", and "who approved these ImageNet labels?"

Nevermind that this particular sampling raises. The point is, I've spent a lot of time as a "vision person" and gotten well and truly into the weeds there. 1 That's why I found myself as surprised as anybody to be almost two years into my time at Noetik, a cancer immunology biotech, and doing some of the most exciting research of my career. In this post I'm going to explain what we're doing at Noetik, where I think this all goes next, and, sure, I'll say whether I think AI will cure cancer.

Disclaimer: these views are mine and mine alone, and don't reflect the position of others at Noetik or the company more broadly.

Why do I work at Noetik?

Reason 1: To try and help cancer patients

The glaringly obvious reason to work at a company trying to improve treatment of cancer is that cancer is a terrible disease. Of course the average person knows that cancer is THE disease that we should all be trying to cure, but it's worth reminding ourselves what we're up against here:

- the number of new cancer cases each year is more than 20M, with the number of annual cancer deaths about half that

- cancer mortality is highest in low-income areas due to lack of early detection and treatment opportunities

- even when cancer is detected, we don't always know how to limit its growth or eliminate it

With respect to this last point, the situation has improved somewhat in recent years due to the rise of immunotherapies: treatments that support the patient's own immune system in recognizing and attacking tumors. Unfortunately even this promising new class of treatments is not guaranteed to work for every patient, to put things mildly. A big part of the problem is that even when we find a drug that works astonishingly well for some people, we can't easily predict who those "responders" will be ahead of time. The reasons for this are understandable: the efficacy of a drug can depend on patient-specific idiosyncracies that are hard to measure and harder to generalize.

The bet we're making at Noetik is that advanced machine learning methods, fueled by a rich multimodal dataset of tissue samples from real cancer patients, is going to be able to match patients with a drug that will work for them. I won't go into the detailed methods here, but we're quite (unusually?) open about our approach in technical reports on the company website.

The core idea is that we're building "world models", or simulators, of patient tissue that learn the complexity of the tumor-immune microenvironment. We then use those simulators to make detailed predictions about patient biology, including a prediction of how well a given treatment will work for a particular patient's tumor. There's a lot of work to be done here, but I'm very optimistic about this strategy in general.

Reason 2: To build advanced world models

Something I find myself telling people very often is that even if, for whatever reason, you didn't care at all about curing cancer, I believe Noetik would still be a uniquely interesting place to work.

By the time I finished my PhD, the chaotic early days of machine learning had faded into a kind of convergent sameness. Everybody was using the same architectures on the same datasets, and competing for fractions of a percent improvement on the same tasks. There was also a looming feeling that academic labs or smaller organizations were going to get depressingly outcompeted by huge companies with massive budgets. If the answer to having a better vision model is "train on an internet's worth of images", only a few companies can really pull that off, and everyone else is left trying to make sense of toy models.

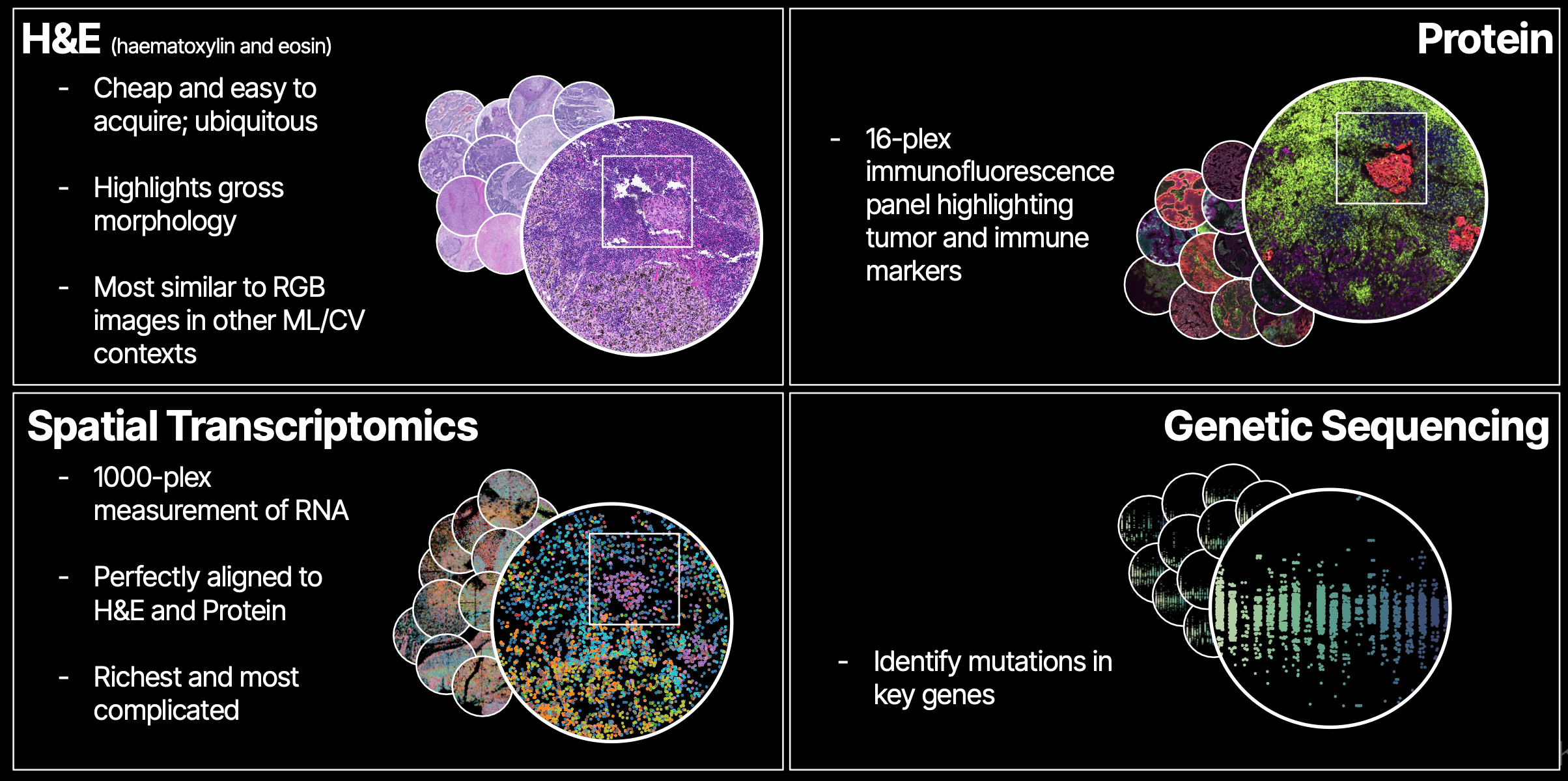

The situation in biotech right now is different in almost every way: there is not even a hint of consensus about the best dataset, task, or model architecture to use for pretraining, and there's even less agreement about how to use models for therapeutics once they're trained. Noetik has taken an opinionated stance on these questions: we generate a large multimodal dataset from real patient tumor samples, and train transformer-based foundation models on those data.

As an ML scientist, this puts me in the following position:

- There is a continuous stream of data coming out of our lab in South San Francisco, expanding the breadth and depth of our dataset. Every time we train a new model, there is slightly more and slightly richer data to learn from.

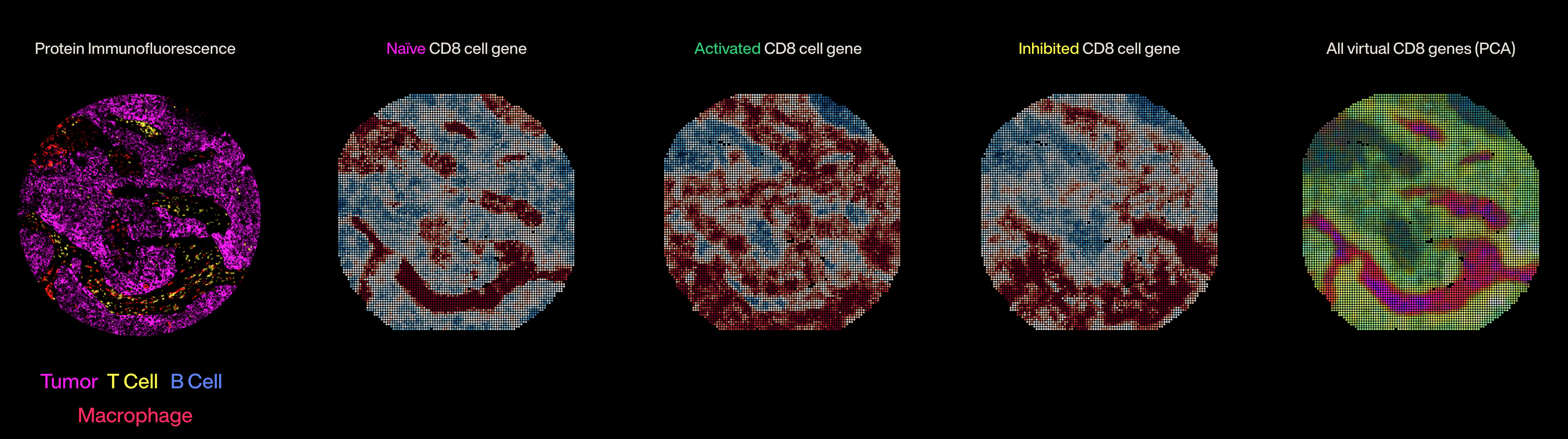

- The dataset is composed of densely multimodal data, such that any given area of a patient's tissue has spatially-aligned data from each modality. This allows for some really fun and wacky architectures that route information through bottlenecks designed to force the model to, for example, learn about some region in Modality A from an adjacent region in Modality B.

- Once models are trained, we can directly use them to ask questions like: "are we able to predict which patients responded to some treatment in a clinical trial?". The feedback loop to the company mission is immediate.

This is, to say the least, as fun as it is challenging. If you'd like to hear more about what we're building, this talk I gave at Stanford's Transformers United seminar (May 2025) is a good entry point.

Will AI cure cancer?

By now you've probably heard "well AI could cure cancer!" as a defense of the pursuit of AGI, and often as a rebuttal to criticisms about the social and environmental issues created by scaling demands. I think it's important to engage with this question critically, because if we think AI (or AGI?) will cure cancer, our risk tolerance for negative side effects really should be adjusted accordingly.

My perspective as someone working in this field is that we are probably not going to completely eradicate cancer with AI within the next few years, and I don't think that LLMs falling short of AGI is the biggest barrier. I do think that we can dramatically improve the way we identify successful treatment regimes for any given patient, such that many more cancers are effectively managed much earlier in a patient's treamtent timeline.

How could this plausibly happen? I think there are basically two options:

- LLMs get so smart and powerful that they quickly exceed human capacity to do basic research. In this universe, LLMs leverage vast knowledge of the literature and strong reasoning skills to figure out exactly what is causing cancer and how to prevent and treat it. I am not super opimistic about things working out this way, but my "error bars" are large -- things are changing quickly!

- Foundation models trained on a rich picture of patient biology enable scientists to craft, run, and analyze large-scale simulations of patient tissue. In this universe, a scientist can ask questions like "if I antagonize protein X, will the immune system better infiltrate the tumor?", and get answers that are conditioned on a specific patient's biology.

Option 2 doesn't preclude the utility of LLMs; in fact, I think LLMs are going to be great scientific partners in surfacing relevant literature and helping craft analyses. The difference I'm drawing attention to is in which foundational system we invest time and money: the text-based LLM, or the patient-data-based world model.

In any case, the recent rate of progress in large-scale machine learning has been astounding, and a genuine reason to be optimistic. It's very hard for me to imagine a world in which five years have gone by without AI making a real, tangible impact on patient treatment outcomes.

Footnotes

-

As a vision person, I have to point out the pattern of these apparent labeling errors: there are many more people than you'd expect from the breakdown of the ImageNet categories! This is something I found myself explaining to people quite a lot: even though ImageNet has very few categories that should have people, the dataset is just crawling with them. This is part of my explanation for why face-selective artificial neurons reliably emerge in networks trained on ImageNet. ↩