What I learned reading a paper each week for 4 years

A peri-pandemic paper-profiling project

2020 was not a good year for me. Amplified by the horrific unprecedentedness of the pandemic, I found myself 3 years into a PhD feeling the way most grad students do at that point: profoundly stuck. I had finished my required coursework and passed my qualifying exams, but still felt like I had an embarrasingly tenuous grasp on the literature in my field, both current and historical. I didn't know what I didn't know, and my job was to discover things that nobody knows yet! Now compound that feeling with the pervasive feeling that everybody except for you knows about every paper ever published -- the old timers in the department rattle off citations from 40 years ago while the summer intern, fresh out of middle school, is asking your opinions on preprints uploaded 17 minutes ago.

My diagnosis at the time was that I just wasn't reading enough papers. This would turn out to be mostly inaccurate, and I would come to realize that everybody was sort of regurgitating common wisdom (or hot takes on Twitter) instead of actually reading stuff, but my mistake led me down a very Eshedian path: I decided to commit to reading and taking notes on one relevant paper each week. Over time I decided to 1) make these notes public, and 2) distract myself from research with a side project to make regular note-taking possible for others as well.

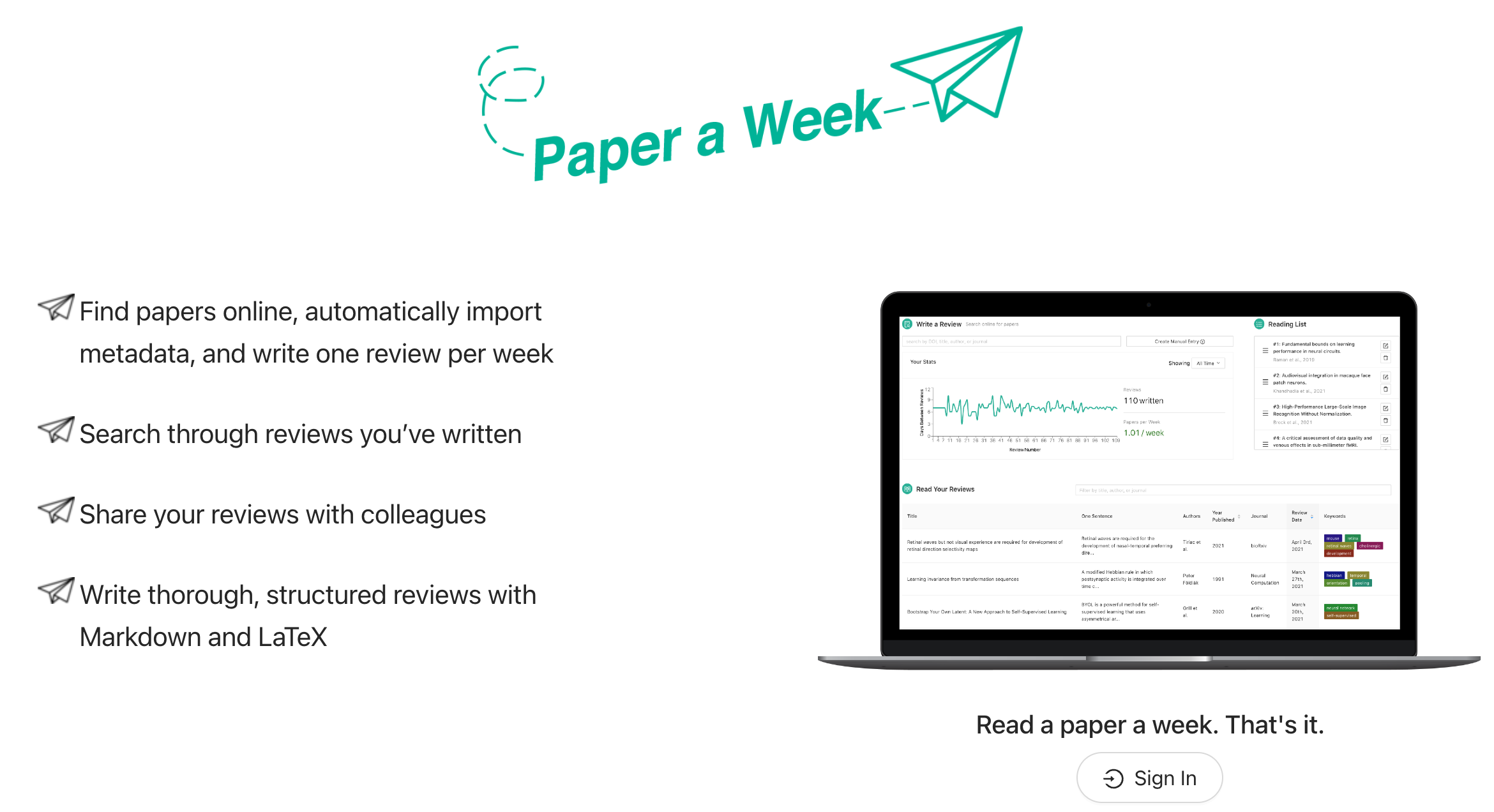

This led to the creation of Paper a Week, a web app to facilitate taking notes on academic papers.

The feature set is minimal but powerful:

- There's a search tool integrated with OpenAlex so you can find papers and their metadata easily

- You can maintain an ordered reading list

- There's a habit tracker showing your weekly review rate

- Reviews can be written with markdown and LaTeX syntax

- You can share your reviews, if you want. Here are mine!

I ended up reviewing 200 papers in 200 weeks, so a bit under 4 years.

What I learned

Peer review is very weird and mostly a good thing

Academics complain a lot about peer review, and for good reason. As a reviewer, it's basically unpaid labor to try and figure out how the authors are lying to you. As an author, it's a never ending gauntlet of explaining the same points over and over. But my main takeaway after 200 papers is that peer review is largely effective, and its continued use is something of a miracle. Most authors will attest that peer review strengthens their logic, helps weed out confusing terminology/jargon, and acts as a filter against the most egregious deception and the most painfully verbose rants.

This becomes especially apparent when you compare a field like neuroscience to a field like machine learning -- the presence of a robust peer review system (meaning, not random undergrads that coauthored a paper once) makes the expected value of reading a paper much higher.

Everybody wants to read papers, but nobody wants to read papers

As I recounted above, grad school is overflowing with people scrambling to cite foundational pillars or cutting edge novel papers. The motivation is obvious: you can look really smart and well-read by doing so, and a disturbingly large portion of academia is signaling that you're really smart and well-read. But when you actually talk to people, you realize that almost nobody is reading papers. Okay, if you reclassify "skimmed the figures" as reading papers, the numbers go up a bit. But really, almost nobody is reading papers. That raises a good question about the overall purpose and incentive structure for academic publishing, but that's a topic for a day where I'm feeling mean. There is one notable exception: people read papers when it's extremely relevant to their own work, or in more dramatic cases, when it challenges one of their existing papers. In that case, dissecting a paper critically is of the utmost (sociopolitical) importance.

The reasons people don't want to read papers are not surprising. Reading papers takes time, papers have increasingly become monstrously bloated data dumps, and the paper authors are actively working to lead you to a conclusion while shuffling important technical nuance under the rug. This is normally the part where I'd suggest a solution, but I don't have one. Maybe LLMs will actually help here, but I'm worried that authors will just write their papers to be LLM-friendly even more than they already do.

As an author, the best way to fight against this anti-reading bias is to seek opportunities to present your work as part of a talk, poster, or conference. Advertisement works, and if done well, it doesn't have to make you feel like a sweaty used car salesperson. Before the great Twitter exodus, "tweeprints" were a great example of advertising a paper to peers in a more accessible way than linking to a triple-paywalled article.

Choosing which papers to read is 80% of reading papers

Everybody wants to read papers, but nobody tells you how to pick which papers to read. Here's my recommendation:

- For every 2 papers you read that have been published in the past 10 years, closely read a huge foundational paper in your field. These are often fun, or surprising, or inspiring. They might also induce rage as you realize how simple research could be in 1967 and still get published in Nature. The other big takeaway for me was that people simply had more modesty about their results back then, and I respect that old-school humility.

- Use Connected Papers to trace through the big papers that came before/after something you found interesting or relevant. It's a very powerful tool.

- You can sometimes find peer reviews published alongside an article. Writing notes on these papers first and then reading what other scientists thought can be a good way to sharpen critical thinking and catch logical gaps that you missed. A good journal for this in my field has been eLife.

Developing neural systems are extraordinarily cool

Okay, enough complaining about the state of academic publishing. I learned some extremely cool stuff while reading all of these papers! Here are some of my favorites:

- The Agouti is a weirdly big and unusually cute rodent. It's useful for visual neuroscientists to study, because people argue about whether mouse and rat brains look different from ours because they are rodents, or because they are small. A big rodent helps break the tie (capybaras are often referenced here too). Ferreiro et al. show that neurons in agouti primary visual cortex are unusually selective for stimulus orientation and direction, but those neurons are not organized into the beautiful topographic maps we observe in animals like cats and monkeys.

- The first paper I reviewed in this streak was Potential downside of high initial visual acuity by Lukas Vogelsang and colleagues. It's a counterintuitive study that runs a developmental neuroscience experiment in silico, showing that curricularizing visual inputs by blurring images early in training can improve model performance.

- There have been some ethically dubious experiments on ferrets with very interesting results: in 1997, Weliky and Katz demonstrated that if you surgically implant an electrical cuff around the optic nerve of a developing ferret and interfere with the natural pattern of spontaneous retinal activity, neurons in primary visual cortex become less orientation selective than in controls, although the spatial pattern of orientation selectivity was preserved. Then, in 2011, Ohshiro et al., demonstrated that raising ferrets in an environment devoid of any oriented lines does not prevent the development of orientation selective neurons in primary visual cortex. It appears the brain really wants primary visual cortex neurons to be orientation selective and organized into maps.

What I didn't learn

There's a lot you can learn by reading a lot of papers, but I discovered a few blind spots along the way that are good to watch out for:

- The actual nature of multiple rounds of peer review is often not visible by just reading the final publication, and until you experience it from either side it's hard to get a feel for the norms and expectations. That's putting aside all the mess about cover letters, how to respond to reviewers, etc.

- Once you've discovered a cluster of papers, it's easy to get stuck visiting each node in that small-world network, but there are diminishing returns there. Asking other people for recommendations can be a good way to get unstuck and find a new cluster to wander in for a few weeks.

- Even after all that reading, I didn't get much faster at digesting papers. I'm a little better now at just skimming a paper and getting what I need out of it, but I still find that until I slow down and read the whole thing, there are going to be critical details I miss.

Should you read a paper each week for 4 years?

If the answer isn't obviously "No, what the heck, are you insane", then I think you should consider some version of it, at least for a few weeks. The streak-preserving aspect made it fun for me, and I think it's a good thing for folks to read papers and share their thoughts on them. I also think it's one of the only ways to really refine your taste in research and decide which approaches (both methods-related and meta-scientific-philosophical) really resonate with you.

The truth is that I don't really read a paper each week anymore. Life got busy, I got distracted, and it felt harder to find high-quality stuff that I wasn't already aware of. But I can honestly say I'm very glad I went down this road, and am still on the lookout for the next streak to cultivate.